Today I want to talk about one thing: the power of editing.

It is the one film discipline that is arguably the hardest to judge. How can you tell if a film is cut well? I’m a veteran film editor of twenty plus years and I can’t tell you. At least not by simply watching the final version of a film.

But I can show you the process.

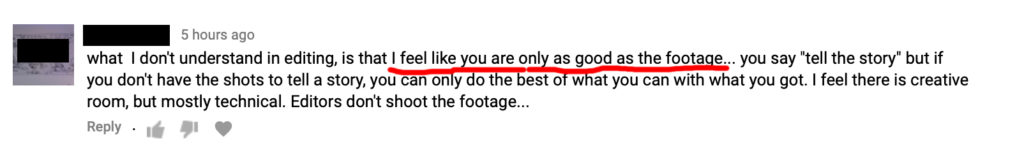

A lot of people think editing is this:

“You are only as good as the footage…you can only do the best of what you can with what you got.”

I hear this quite frequently on my YouTube channel THIS GUY EDITS, where we aim to celebrate the invisible art. It makes sense, right?

I’d dare to say that a lot of people would agree with that statement. However, I don’t see shots as the end of my possibilities, but rather the beginning. If you are following my channel, you might have heard me say this repeatedly: shots are building blocks, and what you do with them is what makes you an editor.

I’ll explain with an example.

I recently cut the film The Ever After, directed by Sundance filmmaker Mark Webber. It was our second collaboration and he was kind enough to provide some of my editing students with film footage from a few scenes.

I ask the students to intercut two actors talking over the phone.

The character Mark is calling his wife, Teresa, in Los Angeles. He has just arrived in New York to do a fancy model shoot the next day. He checks in with her to let her know that he arrived safely.

Somewhere early in the conversation, they go from:

Teresa: “How is it?”

Mark: “Mhm, it’s the same,

pretty much everything is the same.

I think we… uh…

we had this room before.”

Teresa: ”So do you have plans tonight? Are you gonna go out?”

So the student cut the scene according to the script and how it was faithfully performed by the actors. It was a solid cut and, on the surface, there was very little for me to complain about.

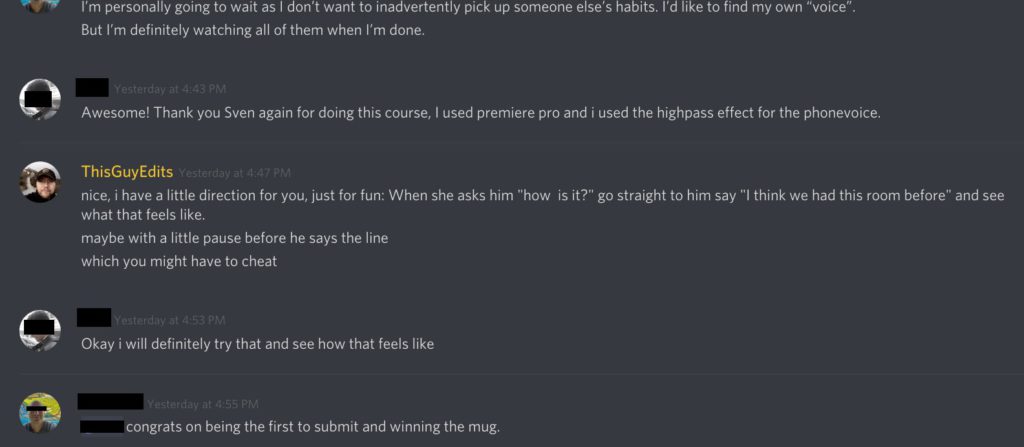

So, I praised the student, then gave him one adjustment. I asked him to make a simple change in the scene:

Take out Mark’s first two lines, add a little breath (a pause) before we come in on Mark saying: “We had this room before.”

That small change created a whole new subtext for the scene.

Teresa: “How is it?”

Mark (pauses): “We had this room before.”

Teresa: “So do you have plans tonight? Are you gonna go out?”

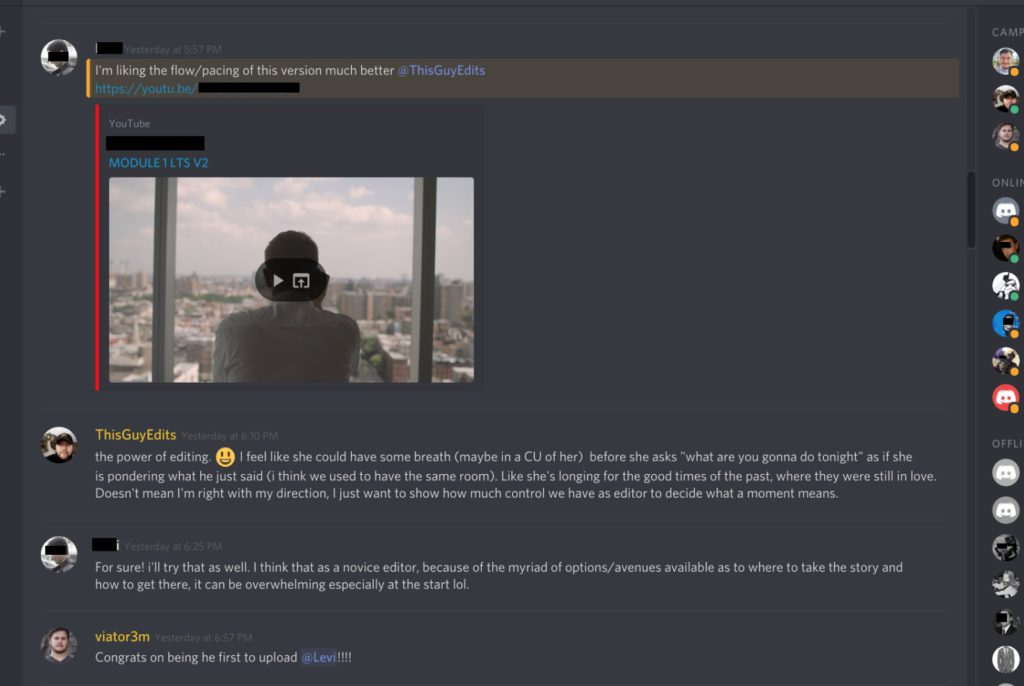

A scene that was on the surface about Teresa catching up with her husband now was about their relationship.

But, the scene wasn’t quite there yet. I asked the student to try putting a longer pause before Teresa answers back.

Teresa: “How is it?”

Mark (pause): “We had this room before.”

Teresa (pause) (pause) (pause): “So do you have plans tonight? Are you gonna go out?”

The scene changed dramatically. Now it’s about sadness. Teresa remembers better times, where the two of them were still in love.

These are significant changes in how you tell the story. None of this was discussed on the day the scene was written or when it was shot. This is what editing does, it finds and shapes the story depending on what you want the audience to feel.

If you’d like to see the change in subtext for yourself, I made a video with the three different versions.

An editor (with a well-trained storytelling muscle) makes 1000s of tiny decisions like this before the director even gets to see the scene for the first time.

Yes, if they don’t work for the director, they are going to change.

But, this shows you how shots are building blocks. And you decide if, when, and how long you let them play.

Performance is not a performance until the editor shapes it to fit with the rest of the film.

Russian filmmaker Pudovkin (1893-1953) went so far as to say that the emotional content of a scene comes more from proper editing technique than it does from the performance of the actor. You may not know Pudovkin, but Stanley Kubrick points to him as his prime influence on technique.

Most people outside the craft of editing are utterly unaware of this power. And even some beginning editors might be, too. They cut shots together with the intent of merely documenting what was recorded.

As your storytelling muscle grows you realize that your job as an editor is to take any shot and manipulate it in a way that it creates a story you can see playing in your head.

- You’ll take a reaction from the beginning of the scene and use it at the end to make a new point.

- You’ll remove lines so that the actor doesn’t just share information, but make us feel the subtext.

- You’ll switch the lines around.

- You’ll use a micro-gesture, one the actor gives off before the director said “action”.

I genuinely believe that the footage has a mind of its own. If you’ve trained yourself to watch and listen, you can imagine how it’s all going to come together.

Dr. Karen Pearlman refers to this phenomena in her book “Cutting Rhythms – Intuitive Editing” as the “extended mind” (introduced initially by Andy Clark).

The shot is part of your thinking.