Part 1: Taking creative control

If you’re reading this, you’re probably a little bit like me. You have a creative itch that needs scratching. That itch motivated me to quit a secure job in IT five years ago and go back to college to study multimedia. I was tired of watching other people’s stories on Netflix. I wanted to make something for myself.

In the following years, I found myself working on all manner of video productions. Sometimes as a producer, other times an editor, and even as just a runner on set. There were student films, and there were larger productions from the past three years working in political communications for the European Union, in Belgium. Although I learned a great deal from all of these projects, a nagging feeling remained: I did not have complete creative control over my work.

Working as part of a production crew means, to some extent, compromising or adapting your artistic vision to collaborate with others. Oftentimes, you might not even be pursuing your own vision as much as someone else’s. Working for a political institution like the European Union means representing the values and policies of that institution. Creativity does not expire in political comms; but it must find expression within the confines of bureaucracy, which in itself forms an interesting challenge.

As a video editor working in social media, even at my most creative, I was usually confined to 60-second, square-format videos which stayed on message. So on buying a camera 18 months ago, I finally had the opportunity to take complete creative control over a project. For the first time, no other people, political body or format would influence my work. I was curious to know: what did I have in my locker? What was I capable of producing when left to my own devices?

Finding inspiration in Ireland

What followed was one month of glorious inaction. As dust gathered on my new camera, my guilt grew greater every day. Why had I invested so much money in this thing? What about my non-existent savings? I shared my concerns with a colleague and we brainstormed.

Eighteen months ago, Brexit and the question of the Irish border were dominating the news cycle in Europe. As an Irishman, I decided my project should go some way to reflecting our times. So I looked at Northern Ireland, which is a part of Britain. As a native Dubliner, and therefore a Southerner, I never spent much time in the North. In the midst of Brexit, I decided my topic should be relevant to all of Ireland. My colleague suggested the famous political murals there; the ones painted by Unionists who want to remain in Britain, and Republicans who want to unify with the rest of Ireland.

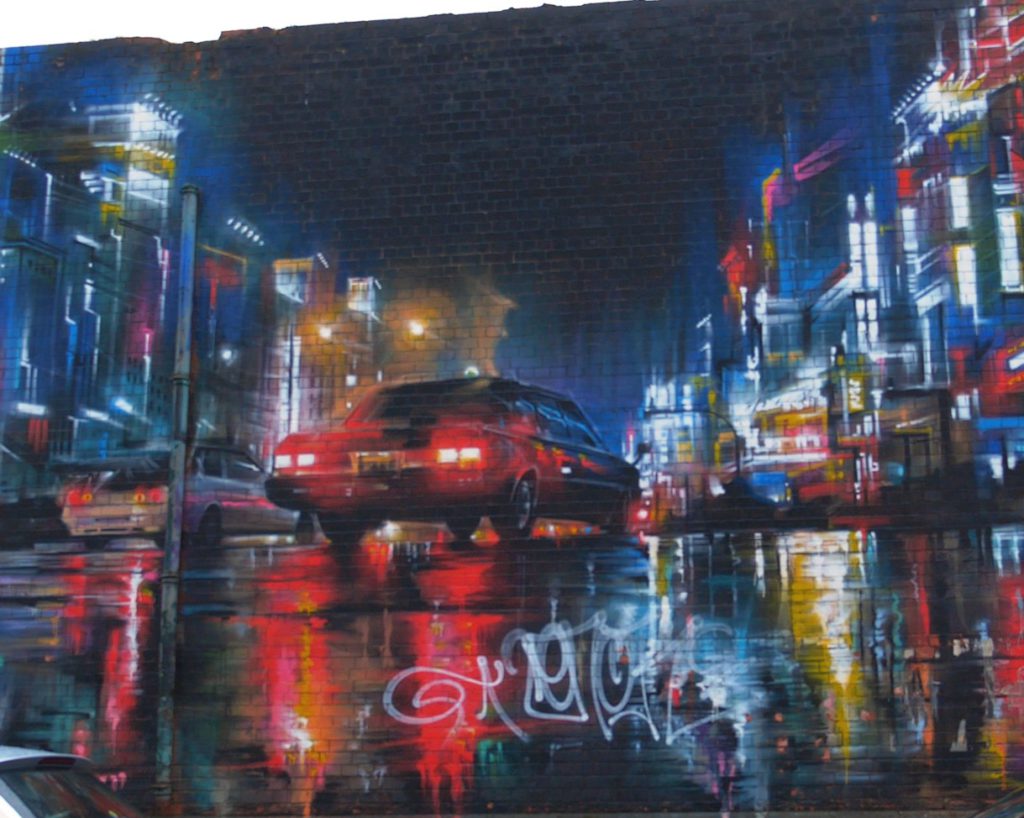

Taking to YouTube, I found documentaries on the old political murals. It seemed that this road was already well travelled by the media and other filmmakers. Then I read an article about a group of street artists in Belfast who were creating vibrant new art in the centre of the city. They differentiated themselves from the political muralists in the sectarian communities. These artists were paving another path for those who chose not to align themselves along old tribal lines.

Artist: ADW

Artist: Dan Kitchener

Artist: Christina Angelina

Artist: SANCHO

This community had some media coverage, but nowhere near the amount given to the old murals. Now, this felt fresh and worth exploring. I decided to make a documentary about these street artists.

Part 2: Just do it

With Belfast locked in, I still wanted to explore another city in Ireland for contrast. As it was my hometown, Dublin was the logical choice. With me living in Brussels at the time, it would have been impractical not to choose the city where I could stay in my family home. I was already taking most of my holidays to come back and film. Considering I was going to be lugging equipment around Belfast, I did not have the money, time or resources to go further afield.

Location scouting and sourcing interviews

I began to research artists in both cities through Google. I wanted to understand their art, passions and the challenges they faced. I looked at their Instagram pages, read articles and watched old interviews to try and understand their artistic world. I contacted a few recurring names from my research. They proved responsive and shared their opinions and tips on the right people to talk to. Using online maps and listicles, I also located the best art to film in each city.

Before long, I had a hit list of artists and their art, and began arranging interview dates. Some names were bigger than others, but generally, I found sending a polite and courteous message usually resulted in people agreeing to meet me. Was I a little intimidated to cold call some of Ireland’s best artists and organise one on one video interviews? Sure, but I still did it anyway. Even if it all ended in disaster, it might make for a good story one day. At least I could say I gave it a shot.

Every film has its challenges

During production, I learned that another documentary on street art was being produced by Ireland’s national broadcaster. I observed people pitying me when I shared this news, some even lightly suggesting that it was time to throw in the towel; to give up. In fact, it incentivised me to keep going with twice as much conviction.

What I lacked in production budget and scale, I would make up for in being versatile and mobile. I did not have to work within the confines of bureaucracy which comes with being Ireland’s national broadcaster. What I lacked in drones, I would make up for in editorial freedom. If I didn’t have a two camera set up for interviews, I would speak to more subjects so the faces changed frequently. I found myself identifying with Nike’s famous slogan on a concerningly profound level: Just do it.

I kept going because I was confident in my story. It didn’t matter if I was successful or not in getting loads of views, or in convincing an outlet to pick up my work. It was about realising a creative ambition.

In the interviews, my informal approach worked in my favour. Usually, when these artists did press, it was with journalists who worked for established outlets. This can bring a degree of tension or nerves. I, on the other hand, was just a random guy with a camera. In many cases, we made a personal connection which injected a positive energy into our conversations. I have received lots of positive feedback on how at ease the subjects appear. So remember: find the advantages in your disadvantages.

Part 3: The pitfalls of self-production

Working alone is not always easy. It is difficult to keep an eye on the picture, monitor audio levels and interview your participant all at once. I shot wide and in 4K to circumvent this, zooming in to correctly frame each subject in post. A friend directed the film’s opening sequence and provided camera work on a couple of shoots. These occasions really helped ease the burden of self-production.

My work is living proof though, that it is possible to create a documentary largely on your own, if not always advisable. It can be quite lonely taking on a project of this size solo, not to mention expensive. I did not realise I had created a 30-minute documentary until I was in the edit suite. If I had known this in advance, I would likely have pared down the production.

At the same time, I have no regrets because I believe every subject played an important role in contributing to the overall story. If anything, I wish I had spent more time exploring gender imbalance in the street art community, a topic only touched on at the end of the piece. I only realised in post-production how much potential there was to be explored there.

In the end I simply ran out of time and resources. Although I had connections who may have been interested in working on the project, it was too risky to try and coordinate calendars with both them and the artists in the small window of time I had back home in Ireland.

Creating a film I’m truly proud of

Scripting and editing also took time to tease out. I edited the majority of the project on a colleague’s computer because I did not have my own equipment. A benefit of living abroad meant I was forced to take long breaks from production, many months at a time. This gave me time and space to review the interview transcripts and weave narratives befitting of each city’s story.

I always came back with fresh eyes for the edit too. As such, I created a piece which has a natural flow and I am proud of this. The final weeks of production were the hardest. I chased copyright clearances and coloured the piece just as coronavirus hit. In future projects of this nature, I would certainly prefer to work with other people. It is too much work for one person to do alone.

Just this once though, I’ve found real satisfaction in seeing it through by myself, and in gratifyingly scratching that creative itch which led me to quit my job five years ago. The reaction has generally been positive and I think this documentary has real value. Proving to myself that I have the capabilities to create something independently which is engaging and informative has been rewarding.

Full Colour is not technically perfect, but it was never intended to be that. It was more about rolling up sleeves and getting something done. It was about telling a good story and getting new perspectives. On balance, I feel I achieved this. I am very biased of course, so please feel free to judge for yourself! It is written for an international audience, and therefore accessible to anyone. However, I would recommend using subtitles for some of the stronger accents. Enjoy!