Part 1: Getting The Job

The Background

Most commercial jobs come in a variety of ways and I often wonder how a project ends up on my desk. Having worked as a director and cinematographer for almost a decade, the most common scenario is usually one of the following: a colleague recommendation, a client happens to stumble on my work and likes it, or – in more recent years – my agent puts me forward for a gig.

The project at hand is the first one (I can’t recall another) that was offered to me as a direct result of the meticulous care and OCD-like manner I ran my Instagram account. I lived in the United Arab Emirates at the time, a small market burgeoning with commercial projects and a limited pool of creative talents; an ideal combination to fast track one’s career into bigger and better things.

One fine morning in July, the following brief arrived in the mail from a trusted production company. I am paraphrasing, but this is essentially what it said: “Jaguar wants to collaborate with various photographers in the region. They like your Instagram and would like you to pitch on the brief”.

Any director is aware of this odd catch 22 in the industry: it’s very difficult to get car jobs if you don’t already have car jobs on your reel. And at that point in time, I had not done any commercials involving a major car brand that I could put on my showreel. But, this email essentially contained a golden opportunity, the type you need to capitalize on. It didn’t matter that I do not consider myself a professional photographer… but more on that later.

The Concept

And so it began… The next step when you receive an email like this, after performing a victory dance in your living room, is to summon the inspiration gods and come up with the best possible idea to detail in a treatment.

Let’s keep in mind that this particular gig was a bit of an oddity. Technically, even though I had to pitch a solid concept to win the job, I knew the client already wanted me to work on their campaign. This is a great advantage that you rarely have. In other words, the project was mine to lose.

There is no obvious method to dissect where an idea comes from and I could write an entirely different post on how to keep yourself inspired and in a healthy creative mind. The brief from the agency should always be the spark that ignites your senses. This time, said brief was open-ended: the client essentially wanted to create a series of images that were unique, with the main criteria being that they had to come from the artist, and obviously, involve their vehicles.

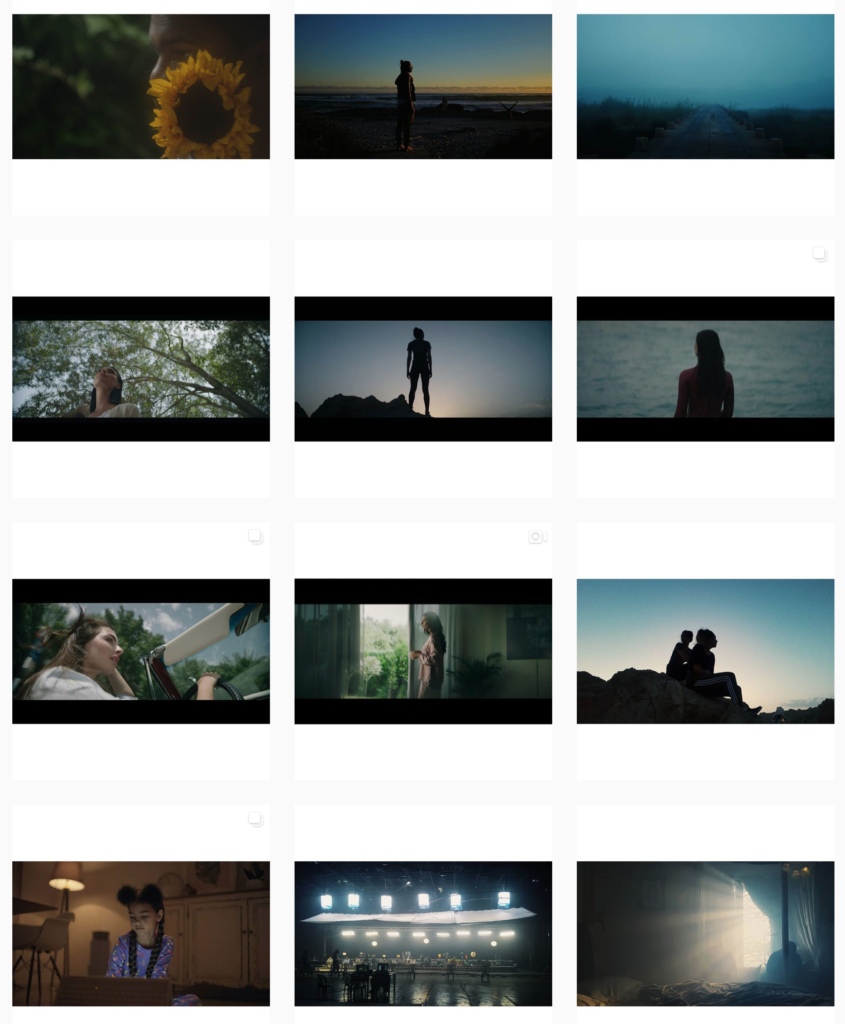

In a nutshell, I wanted to capture the feeling of driving a Jaguar. After a bit of research, I decided that my images should all be linked to the four Classical Elements ancient civilizations believed were the source of all things. A car drives on earth, pierces through the air, advances under rain water, its engine fuelled by fire… What remained, the feeling of driving the car, the unexplainable force that binds it all together, would be the fifth element, known as aether.

Not only did the concept resonate with the brand and the brief, but it also lent itself to some extremely cool visuals. Moreover, as the job was primarily a photography gig, I wanted a concept that I could easily apply to both stills and video. Early on, I decided to use this opportunity to create a television commercial (TVC) of my own, one I could use “for the reel”.

I then gathered a multitude of visual references, pulling stills from existing car commercials, Pinterest, photographers’ portfolios, etc. and presented them in a treatment, along with formulaic words detailing the idea. The client liked it.

Part 2: Making It Happen

The Prep

Once the client approved my treatment, we agreed on a budget and decided to go ahead with the project. I was given a few weeks to prepare. I had decided to shoot the stills portion of the project on 35mm film, which was both intriguing for me on a creative level, and a challenge as I didn’t own a strong analog camera and only had limited experience shooting celluloid.

I bought myself a Nikon F4 – a solid hybrid body that could shoot film with all the bells and whistles of a modern digital camera – along with a few rolls of 35 and began testing. I rapidly got into the groove of shooting analog and I knew I had found the right tool for the job with the F4. For the video, since it was never truly a part of the brief, it was difficult to justify budgeting for additional equipment. I opted to bring on my Red Scarlet-W camera and rented a 40mm Kowa Anamorphic lens as well as an easy rig with my own money.

Crew wise, I decided to stick with a more typical commercial team. Rather than bring on photography assistants and equipment, I wanted to light the stills in the same way I would approach a moving scene. I booked a gaffer and several sparks, a camera assistant, as well as a fairly extensive special effects team to create the fire, rain, earth and wind environments needed for the visuals.

The Shoot

The production had budgeted for a 3-day shoot, which felt like a bit of a luxury. The reason is that we needed to travel across several Emirates, which involved hours of driving between locations. I wanted to find otherworldly places to capture the visuals for the campaign, and stay away from the high rises and modern neighborhoods that were more typical of car commercials from the region. For this, I needed grit! We found some truly great spots in our scouting days, that included an abandoned building, a metal factory, and a rarely used highway underpass in the middle of the desert.

Shooting film photography on such a project was one of the most refreshing experiences I’ve ever had on a set. The rhythm afforded by not stopping after every shot to discuss the images with clients meant that I felt truly free to try different things; I was able to be spontaneous and allow creative thinking and instinct drive my decisions without interference. Because every still was captured in an analog way, there was no playback device, no client monitor, no video village. It was just me and the talent, supported by production and a great technical team.

I approached each setup with a written shot list for the still images, and allowed extra time to experiment and react to the light and emotional state I found myself in. Once I felt confident that we had everything with the Nikon F4, I let the clients know that I was going to “freestyle” with my Red, to shoot the scene with a different format, and potentially create a short video to accompany the photography upon release.

To their credit, both the agency and the client were extremely flexible and trusting of my process, and rarely questioned anything that I wanted to try. On the technical side, a big part of the visual language was to have an ethereal quality. I experimented a lot with placing vaseline on my lenses, combined with glass prisms and diffusion filters. The look turned out to be quite unique and aesthetically pleasing.

The three days went by without any major glitch, and I felt confident that we had captured something special for both the stills and video part of the job upon wrapping.

Part 3: The Finishing

The Offline

I shot close to 30 rolls of film and 2 hours of footage from the three-day shoot, which represents quite a high shooting ratio for the 25 stills that were agreed as the deliverables.

I sent all the rolls to be developed and scanned at high resolution, and jumped on a flight the next day to teach a filmmaking workshop in Seattle, WA. I was so excited to take a look at the rushes from the shoot that I took my laptop and several hard drives on the flight, and started editing right away. I always had a clear idea of the pace I hoped to achieve with the film, but deciding what to pack in the short 30 seconds length proved very difficult. I had to be tremendously selective, leaving a vast amount of beautiful shots on the cutting room floor.

By the time I came back from my trip, the offline cut was locked and ready to go. All the still images came back from the lab shortly after, and I proceeded to select and edit my favorite frames to present to the clients.

The Final Touches

After retouching dozens of the very best images from still photography, I was faced with a dilemma when it came to deciding the fate of the commercial film. I was very proud of the offline edit, but since the project was only budgeted for still photography, there was no money left to pay for the rental of the anamorphic lens, my camera, or the many hours of editing I had already put in. But more importantly, there was no money left to complete the post (sound design, color grading, music rights, voice over etc…).

I took it upon myself to show the client the film and attempted to unlock more money from the abyss of their annual budget. Although they clearly loved the offline edit, they simply couldn’t bring more money to the table, and understandably so – this simply was not part of the plan.

This project was always intended to be a strong portfolio piece for me, personally. So, I decided to go ahead and finish it myself. I had written down a voice-over early on, and after a bit of online browsing, I found a freelance voice artist who recorded the text remotely for a small fee.

The sound design was generously done by a company called Mount Audio, who showed interest in collaborating on the film for their own portfolio. They understood the budgeting limitations and did a stellar job creating the entire SFX from scratch.

Finally, my trusted friend and colorist extraordinaire Jacob McKee graciously took on the color timing of the film, and brought all the tones to life with his magic sauce.

Part 4: The Take Aways

This Jaguar project came out as one of my favorite pieces of work to date. It was a dream job from start to finish, mostly because it allowed me to express my creative vision freely.

The commercial market is ambiguous and imperfect in many ways for directors. Ultimately, there is a balance that has to be found between their own vision, the agency brief, and the client’s expectations of a campaign. As a result, many concepts end up diluted under the many opinions that decide the finished product.

This film went on to get me many more gigs that have far surpassed my initial investment. Looking back, I took several lessons away from this project: strive to create your own opportunities, surround yourself with like-minded creatives who trust and push you, don’t be afraid to invest in yourself, plan well, and always leave room for spontaneity!

Watch the finished film.