A little bit of context

If you’ve seen it, you know that it was a 1989 movie about three musicians. Not cool and edgy rock and roll players, but musicians who, however great their dreams may once have been, now find themselves playing hotel lounges – and not the nicer ones, but the ones out by the airport.

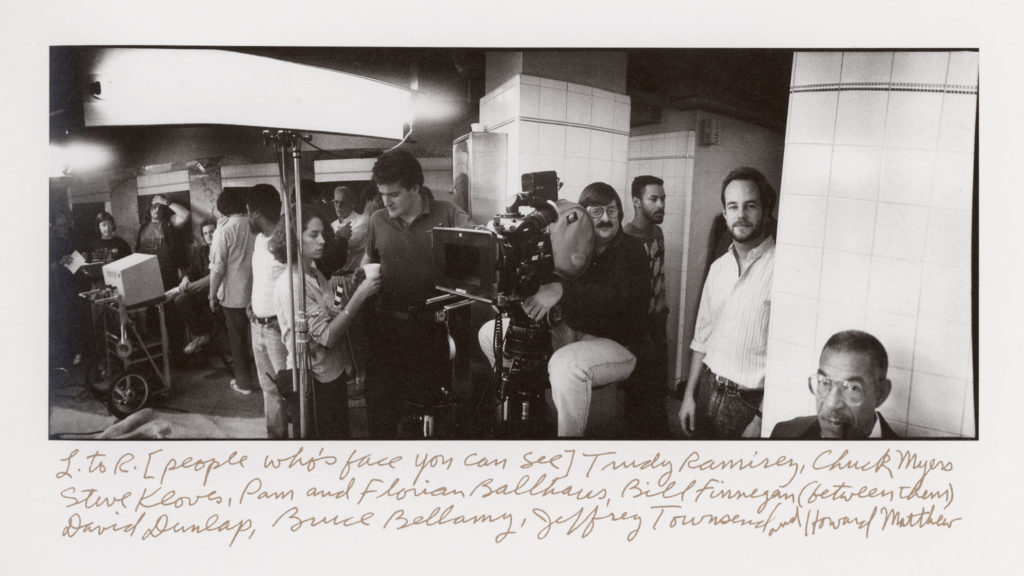

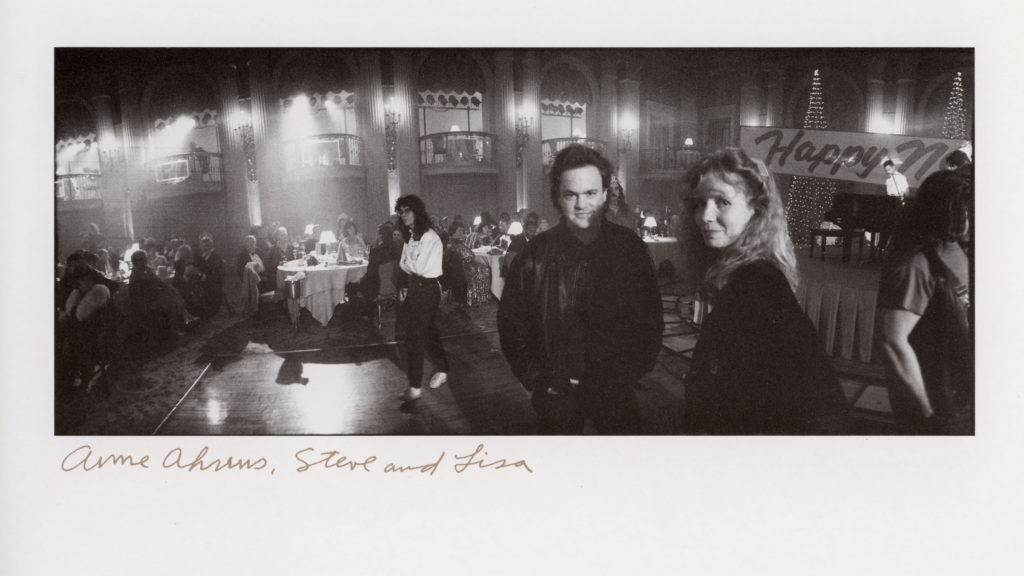

The film was The Fabulous Baker Boys, and I served as its production designer and uncredited second unit director. It was the directing debut of a 27-year-old screenwriter named Steve Kloves, who went on to great success adapting the Harry Potter movies for J. K. Rowling.

It’s a movie suffused with melancholy, populated by characters who have been pummeled by life and still keep going. But, the script had a turning point in the second act, which needed to suggest a new hope for the musicians; a different trajectory for their story.

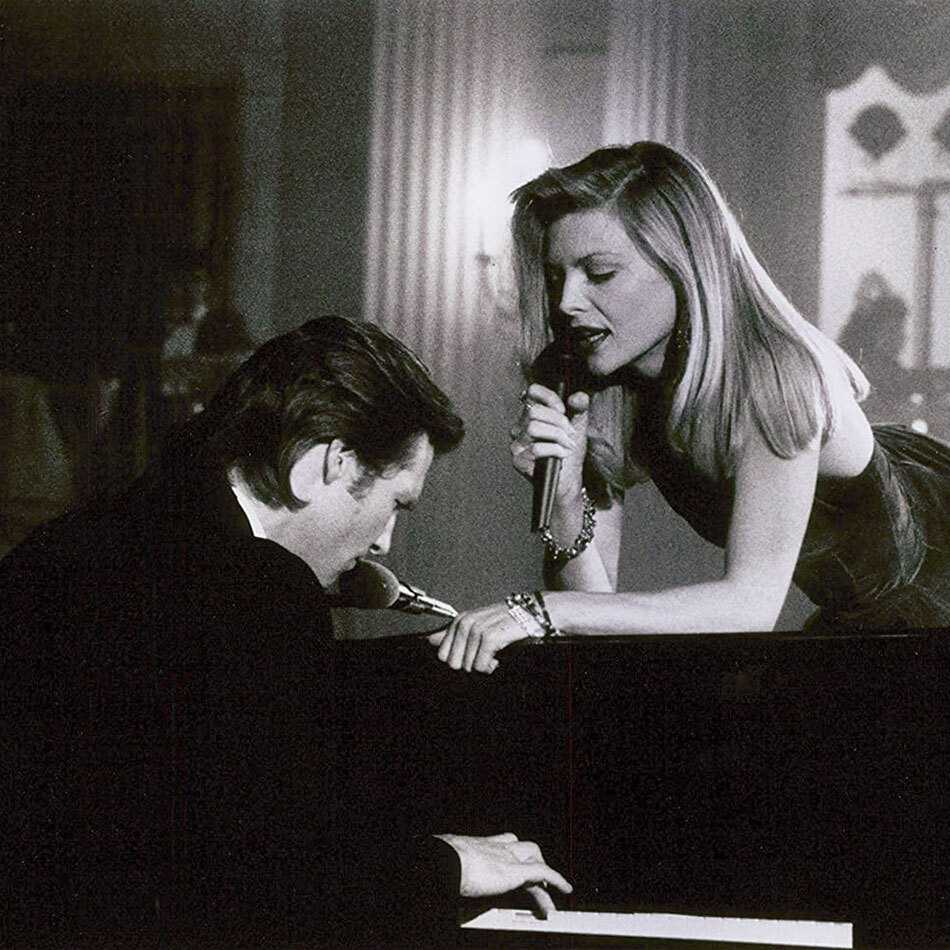

In a well-conceived scene, Kloves had Jeff Bridges (as Jack Baker) and Michelle Pfeiffer (as Susie Diamond) playing a New Year’s Eve gig without Jack’s brother, Frank (played by Beau Bridges, Jeff’s real-life brother). In the story, the sexual chemistry between Jack and Susie had been building for quite some time, along with the feeling that everything – the possibility of romance, and the potential for some really good music – was being held in check by Frank, the sensible brother. But, since Frank had to bail on the New Year’s Eve gig, Jack and Susie decide to bust out some tunes on their own.

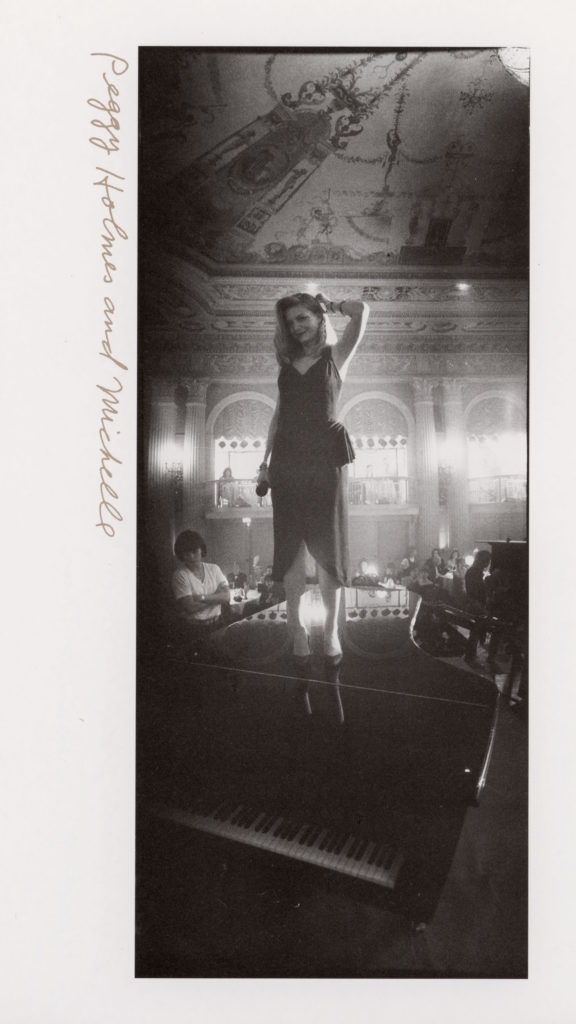

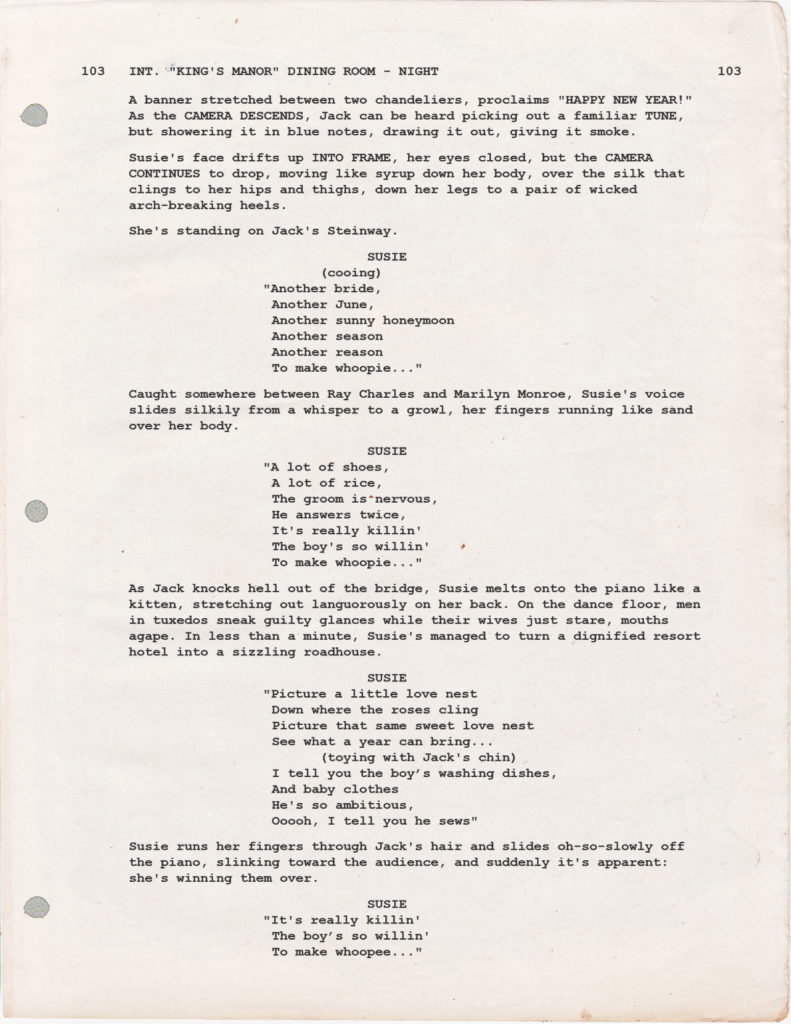

The script always had Susie standing on the grand piano, singing Making Whoopee with sultry abandon. Getting that scene to earn its place as a major turning point in the story, given the movie’s meager budget, took some inspiration.

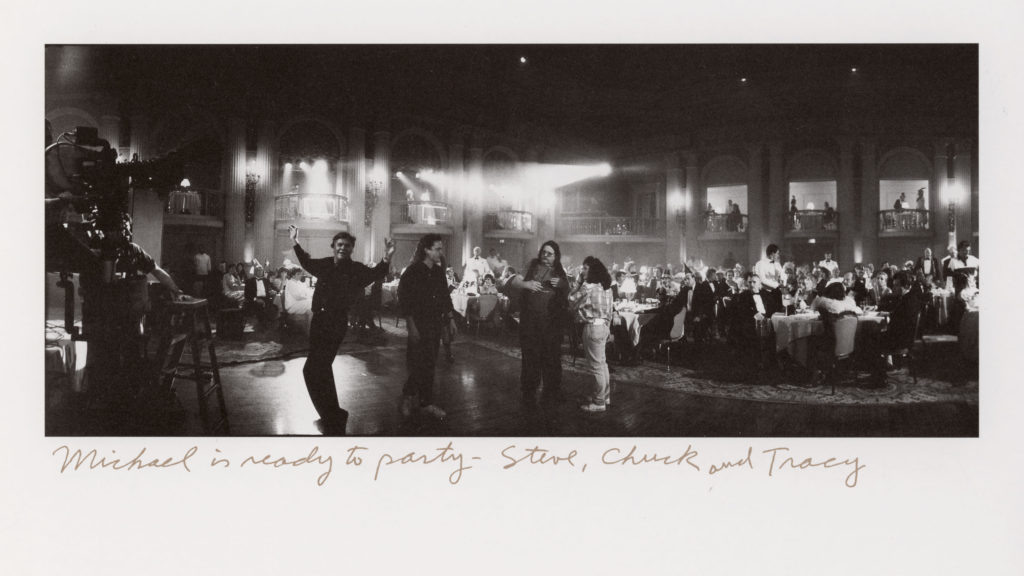

The flashbulb moment came from the late cinematographer Michael Ballhaus (Goodfellas, The Departed). He approached Steve about trying to shoot this key performance scene as a 360-degree continuous take. However, it’s important to explain the treachery that’s tucked inside this beautiful idea.

The producer’s mindset

The primary way that a producer can feel like they are doing the job properly is by looking at the “page count”.” How many pages of the script a day are we burning through during filming? Producers get very nervous if it ever goes below two pages a day. If the crew can maintain the momentum of two pages, two-and-a-half pages, and once in a while a three-page day, you’ve got a happy producer.

The Making Whoopee scene, in the script, was a page long, so a half-day. Most of the page, however, is just the lyrics of the song – so most producers, production managers and first assistant directors would look at that and schedule it for a quarter of a day.

The producer thinks: the song has already been recorded (Michelle Pfeiffer was terrific at lip-syncing to her own recordings), Jeff Bridges has been practicing on a portable keyboard – set up in every location – while watching a video of Dave Grusin’s hands playing each of the tunes in the film, so he was an expert at mimicking Grusin’s movements in time to the pre-recorded track. A few takes from a few angles, and the cast and crew should be moving on to get that page count up to at least two pages.

Except now you have a director and cinematographer telling you they want to shoot the scene as a single, complicated shot. You know some of these headaches from past experiences: where does the crew hide in a 360-degree shot? Where can you light from? It’s a location, not a soundstage set. There’s choreography, lighting, focus issues – so many ways to blow a take and then the whole effort is wasted because it has to work in a single, unedited shot.

Your blood pressure is rising. You have to ask: How long do you think this will take? The answer: a whole day. Instead of two pages a day, the director is asking for permission to slow down to a crawl. Well, they point out, it is a full page in the script.

The nightmare begins

In its execution, this 360-degree shot is the centerpiece of a four-shot sequence.

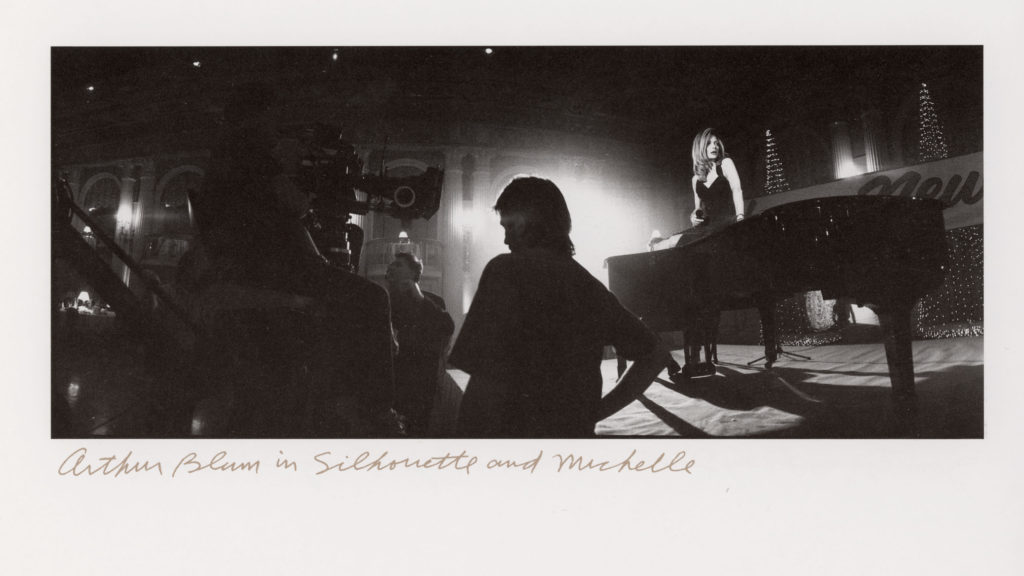

- There’s the opening shot, starting on Pfeiffer’s high heels on a glossy surface, almost in silhouette. The camera rises up her body while she sings the opening verse. Then, as she starts to crouch, the camera pans down to Bridges at the keyboard and we realize that she is on top of the piano.

- On a staccato chord, we cut to Pfeiffer from the front as her head snaps to the audience, ready to sing verse two. This is the beginning of The Shot.

As the camera begins to circle clockwise, the shot begins gently zooming wider, allowing us to see all of Pfeiffer’s reclining figure and eventually including Bridges, too.

As we circle behind Bridges, the camera zooms in slightly as Pfeiffer crawls toward him and sings, directly to him, “Picture a little love nest…” The camera catches a beautiful flare from the spotlight, reflecting off the piano’s glossy surface and enveloping the two actors for a glowing moment.

As the camera continues, now about three-quarters of the way in its single revolution, she rolls onto her back and reaches out like a cat, stroking Bridges on the chin.

The camera zooms out again as Pfeiffer spins gracefully into a seated pose, then zooms in as she leans forward, toward the audience, starting the closing refrain.

As we pass the 360-degree point, there’s a brief cutaway to…

- …the audience, for about three seconds, where even the waiters are staring, slack-jawed…

- …and back to Bridges, ramping up to the finish, as Pfeiffer, out of frame, stands and steps into the shot and the camera settles, finally, no longer circling. Still singing, she steps on the edge of the keyboard and onto the piano bench, joining Bridges for the final reprise and massive applause.

Simple enough, right?

How the pros make whoopee

It took hours to lay the circular dolly track and work through the moves of the camera so that the opposite side of its circumference was always out of shot. I remember having to repeatedly shrink the size of the modular stage platform until it barely held the piano and piano bench. It looked fine within the camera’s frame but very strange from any other vantage point.

Choreographer Peggy Holmes worked with Michelle on the routine, and costume designer Lisa Jensen had to keep an eye on the slit in Michelle’s red dress: it had to be deep enough to allow for all the slyly acrobatic moves, but no deeper. Step by step, the routine and the camera move got incrementally closer to what was needed, but the hours were flying by.

One question was on lots of crew members’ lips: what about the huge scaffolding rig in the corner of the ballroom, where the spotlight and operator are staged? Aren’t we going to see that? This is where Ballhaus and gaffer Jim Tynes eventually revealed their huge gamble: Tynes would operate a massive dimmer for the spotlight, and carefully dial it up in sync with the camera’s movement. It appeared that the camera’s position behind Bridges was causing the beautiful flare on the glossy surface of the piano to obliterate the background, when in fact it was the light itself becoming so much brighter – combined with a light fog treatment in the air – that it could obscure the scaffolding it was set-up on. Genius.

We were closing in on the end of the shooting day, and the crew is still trying to get a usable take. Remember, to a low-budget producer, this is one way to lose your job: a whole shooting day with zero pages of script to show for it. And right now, the thing that’s ruining every take is getting Michelle off the piano at the end of the song.

My art department had already built a wooden cover for the four highest keys on the piano, painted glossy black, that could hold Michelle’s weight without damaging the keys. From the camera’s position, it looked perfectly normal. Her next step, however, to the piano bench, was tending to reveal Ms. Pfeiffer’s underwear for just a moment. This also coincided with seeing Jeff’s piano playing most clearly, for the loose, open-tempo ending. Ultimately, it became too much and Plan B was put into play: they would film a panning reaction shot of the audience so that they could combine the best take of 90 percent of the song with the best take of its ending.

When the dust had settled, the producers had kept their jobs, the exhausted crew and performers were satisfied, and there was one more thing no one foresaw: I have yet to read a single review of the film that does not mention this shot.

Was it worth it? Decide for yourself.

Me? I’m with the critics on this one.